Parkinson’s disease has long been a study in frustration. The tremors that affect patients stem from a shortage of dopamine, a chemical messenger in the brain. Drugs can top up supplies and bring temporary relief, but they do nothing to repair the faulty circuits that cause the loss in the first place.

Deep-brain stimulators — metal electrodes that jolt neurons with electricity — can also help, but often only for a time. Scar tissue eventually builds around the implants, muffling their signals and blunting their effect.

A new approach is now gaining attention: the replacement of the damaged dopamine circuits with “living implants”.

The first prototypes have been created, made from lab-grown brain cells, and modified so that they can be controlled electronically.

Britain has become one of the most ambitious backers of this kind of “biohybrid” technology. The Advanced Research and Invention Agency (Aria) — a government body set up to fund science “on the edge of the possible” — is bankrolling what may be the most audacious effort yet to make the idea a reality.

Among those being supported is Kacy Cullen, a neurosurgeon and bioengineer at the University of Pennsylvania, whose group is getting a share of the £69 million Aria is investing in “precision neurotechnologies”. His team is cultivating strands of nerve tissue no thicker than a human hair made from lab-grown brain cells, or neurons. The plan is to insert these living fibres into the brains of Parkinson’s patients.

The neurons are genetically modified to respond to light. They will release dopamine when stimulated with specific wavelengths.

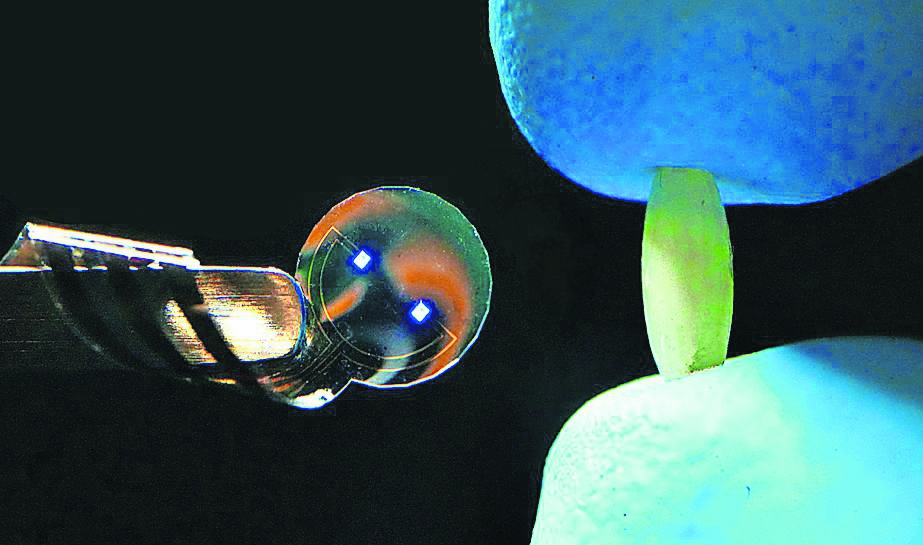

A tiny LED device, about the same size as a grain of rice and designed by Cullen’s collaborator, Professor Flavia Vitale, would sit just beneath the skull — on the brain’s surface, but not inside it — and direct light to the implants when required. By prompting the cells to secrete dopamine on cue, the therapy should ease the movement problems that are a hallmark of the disease.

Unlike the metal electrodes used for traditional brain implants, which can provoke scarring and rejection, these fibres could be derived from a patient’s own skin cells, or from mass-produced cell lines engineered not to rile the recipient’s immune system. If successful, they could integrate seamlessly into brain tissue and function for years.

Cullen’s research overlaps with the efforts of Elon Musk’s company Neuralink, which is putting ultrafine metal electrodes — gold or platinum conductors embedded in polymer threads — into the brains of trial participants.

By monitoring the electrical activity of his brain, the Neuralink system has enabled a paralysed man to control a cursor — but Cullen argues that living implants hold far greater promise. Unlike Neuralink’s passive electrodes, labgrown cells could form synaptic connections with natural neighbours, passing information back and forth.

For Parkinson’s, the target is dopamine production in the brain’s striatum region, where the deficit lies. But similar implants may calm epileptic seizures, rebuild circuits after a stroke or spinal injury or even provide sensory feedback to prosthetic limbs.

Jacques Carolan, Aria’s programme director for precision neurotechnologies, is conscious that “disorders of wiring underpin so many neurological and psychiatric conditions”. He envisages a future where lab-grown neurons can make the right connections to restore mangled circuits.

Cullen estimates that it would be at least five to seven years before human trials could begin for his living dopamine implant, and longer still before any therapy won regulatory clearance.

Scaling up the manufacture of viable tissue, and ensuring it is safe, would be challenging. Even so, he is confident of the trajectory. After decades of pushing metal into the brain, researchers are turning to living technology. “I really think this is the future,” he says.

No comments:

Post a Comment